Jenny’s starts her Waterbiography with memories of her chin-wobbling Aunty Mary taking her to Birmingham’s gloomy Sparkehill Baths for her first lessons in swimming, the only real instructions being to just “get in the water”. Not exactly the most inspiring of starts, but this first dip was to lead to a love affair with water and an exploration of the politics and history of women’s swimming.

Jenny freely admits that her early swimming was hardly enthusiastic, describing her first width at Wyndley Baths as a kind of doggy paddle ‘even though the doggy would have drowned well before it reached its stick’. Then in a prophetic twist, she landed a summer job at its sister outdoor pool, Keeper’s Pool in Sutton Park, running the cafe. She looks back with irony remembering the girls swimming in the pool and thinking “God. How shallow. You won’t catch me doing that”. Little did she know then how much women had to battle to get into that pool, and how much she would learn to love a Lido.

The first know book of swimming was De Arte Natandi, written in 1587 by Sir Everard Digby. All in latin, this scientific tome was hardly accessible to the general public and rather male orientated. At that time the only time women spent in the water was at the end of a ducking chair being accused of witchcraft. This practice was officially ended in 1809 but continued in rural areas until as late as 1864.

The break for women came in the early 1700s when sea bathing became popular as a cure-all for diseases, internal and external. Of course women had to be segregated to another part of the beach from the men to avoid ‘moral dangers’. While the men were allowed the freedom of swimming nude, the poor ladies were weighed down in flannel nighties to preserve their modesty and make swimming pretty much impossible.

It took another 100 years before there were reports of mixed bathing, which at the time was seen as rather bohemian. This was despite some famous Victorian celebrities encouraging the sport including the Queen herself and authoress Jane Austin who were both keen sea swimmers. It was not until 1901 that segregation on Britain’s beaches was legally ended.

Meanwhile the battle for equality was also raging indoors. The 1846 Baths and Washhouses Act enable local authorities to raise money to build pools open to all… meaning men. One of the first pools to admit women into a space exclusively intended for men was Marylebone Baths in 1854, but for one day a week only. This pioneering move was led by authoress Elizabeth Eiloart who called for women to ‘not go about like a floating coffin, but be cheerful and enjoy yourself’.

Although women were still fighting to get in the pool, some real heroines of swimming emerged. Notable examples included the truly fearless Agnes Beckwith. She was the daughter of Champion Swimmer ‘Professor Fredrick Beckwith and first performed to the public at the age of four with the Beckwith Frogs dressed in f’leshings and drawers’ darting around in a glass tank. At the age of fourteen she swam from London Bridge to Greenwich in one hour eight minutes dressed in a bathing costume of ‘rose-pink llama trimmed with lace’. At the age of seventeen she swam a twenty mile swim from Westminster Bridge to Richmond and back, this time dressed in a ‘closely fitted amber suit adorned with white lace, a jaunty straw hat and fluttering blue ribbons’ which took her six hours twenty five minutes. Why the hat?

There followed a string of other incredible female swimmers such as Emily Parker who in 1875 swam London Bridge to Blackwall in just over an hour and a half; Annette Kellerman who in 1905 was the first female swimmer to attempt the channel; Hilda James who was the first woman to swim crawl in Britain, smashing international records and nicknamed The English Comet; Agnes Nicks who swam Teddington to Waterloo and back in thirteen hours setting a new British freshwater record.

One notable battle for emancipation came in 1914 when the suffragettes organised a Water Carnival at the serpentine to protest against the men only swimming races held there. They had announced their intention of taking to the boats, but the authorities had moored them all in the centre of the lake. Undaunted the ladies flung off their clothes revealing their bathing costumes, swam out to the boats to defiantly wave the suffragette flag. It would not be until 1930 that the official lido was built with concomitant changes facilities enabling women to finally get in the water.

And the heroines of the waves kept coming. In 1926 an American swimmer Gertrude Ederle became the first woman to successfully cross the English Channel. This was repeated the following year by the British swimmer Mercedes Gleitze, who had to swim it twice before the authorities would believe her. Then there is Dr Julie Bradshaw who swam the Channel butterfly and Sally Minty-Gravett who completed the swim at the age of fifty nine. And of course the iconic Jackie Cobell with the slowest crossing of twenty eight hours and forty four minutes. She describes how she felt as being “like a pork chop out the freezer”, “I just kept swimming until my tits dragged on the sand”.

Today the ASA statistics show that swimming is the second most popular sport for women. The average woman channel swimmer is 32 minutes faster than the average man. Women are also the backbone of many a swimming club.

So why do women swim? The author describes swimming as a ‘femine art’ ‘It holds us, heals us… We can grieve here, get strong, meditate, take up space… We can be ourselves, liberated’. The simplest explanation seems to be that women swim ‘because they can’.

An enjoyable and thought provoking book, thoroughly recommended.

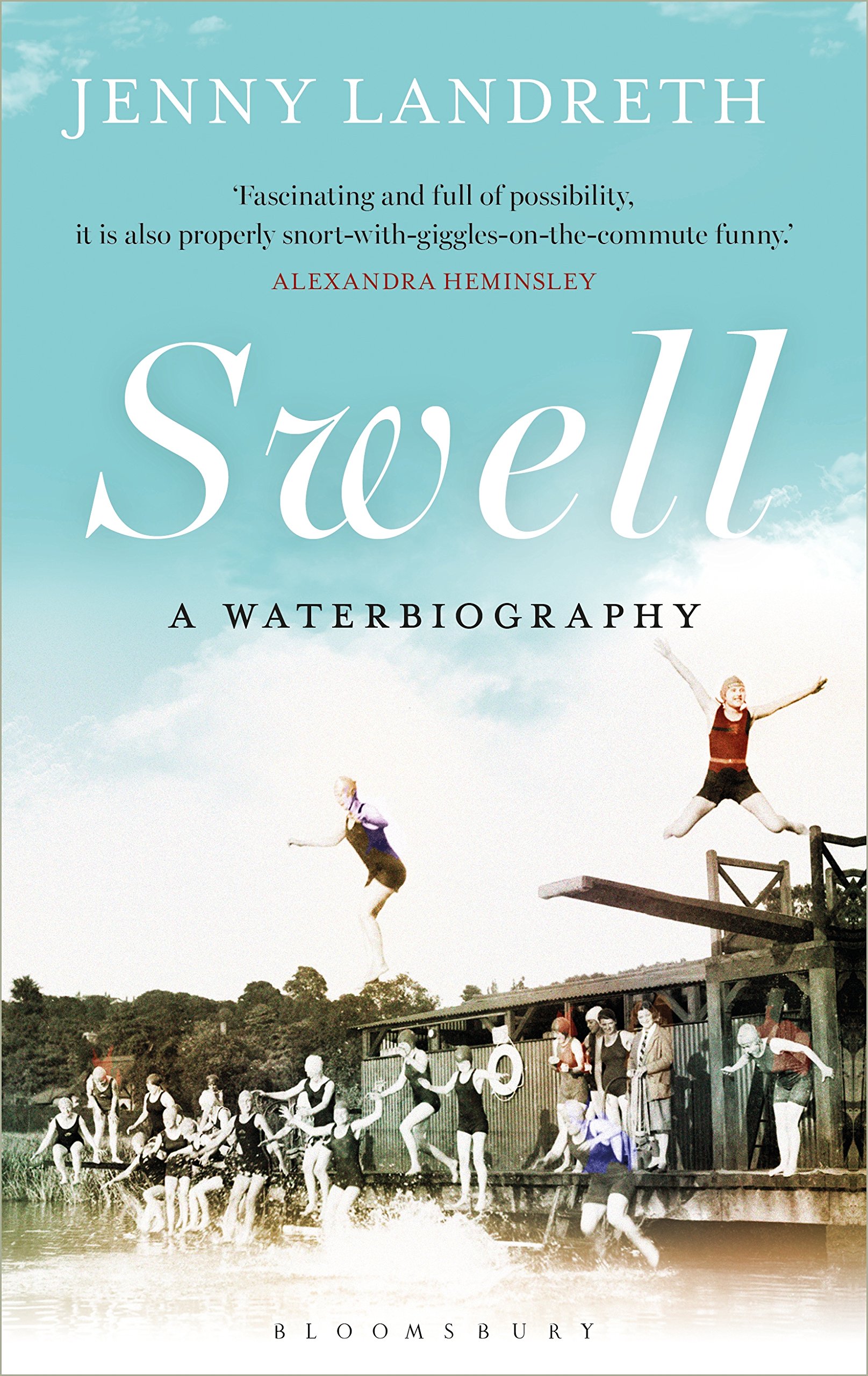

Published: 04-05-2017. ISBN: 9781472938978. Publisher: Bloomsbury Sport. Illustrations: 1 x 16 page colour plate section. www.bloomsbury.com